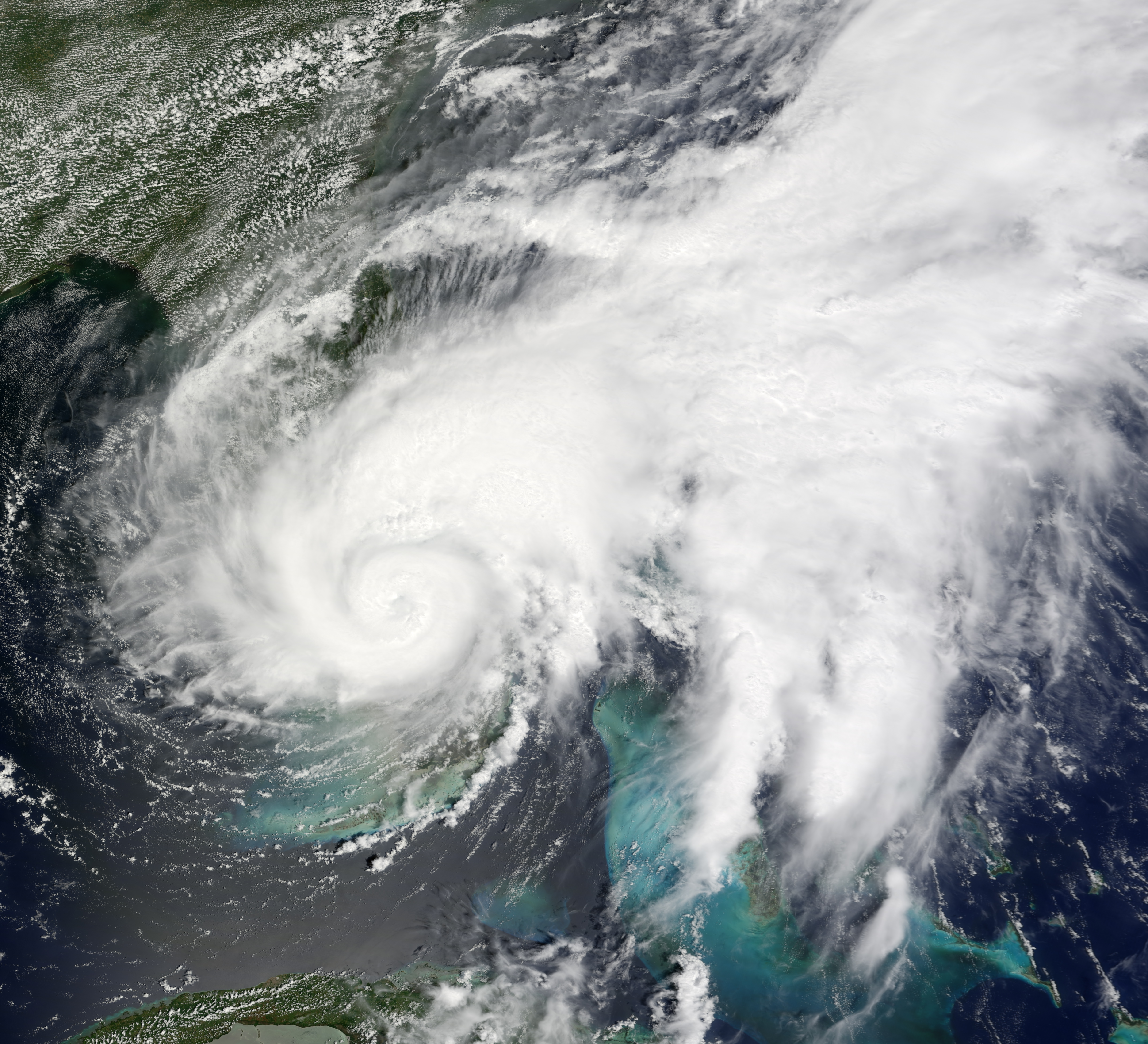

LANDSEA: Well, NOAA's investigating that option, as well. NORRIS: Pardon my ignorance in asking this question, but would it be possible to use unmanned aircraft? And the best way to get that, that we can come up with right now, is with manned reconnaissance: Go in, get the data - especially radar data that has the winds and the rain - and get that into the computer model so that can help us make a better forecast. What we're finding, though, for wind-speed forecasts is, we need detailed information on the inner core - say, the innermost 50 or 100 miles from the eye of the storm. We're also very fortunate in the Atlantic and Gulf area that we have the aircraft reconnaissance that fly into the storms. One of the best ways we do that right now is with satellite imagery. There's no weather balloons, there's no automated ground stations out there, so you got to put resources or instruments in the way of the hurricane to help measure what's going on. LANDSEA: Well, that's part of the tricky issue, is that hurricanes occur over the open ocean. NORRIS: Now, I know that forecasts are based in part on computer modeling, but how do you actually pull data from the field? So it's very much more difficult because of all these different interactions going on.

2008 HURRICANE TRACK PATCH

And it also has to do with whether or not you get wind shear that disrupts the storm, whether you get dry air that sneaks into the inner core and dries out the thunderstorms, and whether you go over a patch of cool water. LANDSEA: It's much more involved with both the ocean and the atmosphere, whereas track predictions, it's all just the atmosphere pushing the hurricane around. NORRIS: So why is it so difficult, of all things to predict or to forecast, the wind speed? So if you go from a one to a four, you're looking at 100 to 150 times the amount of damage that could occur.

Very good news for Louisiana, but it kind of highlights our limitations in issuing skillful wind speed forecasts.Īnd each category goes up - it's especially of concern because roughly the damage increases by a factor of five. Early projections were that it was going to be coming ashore as perhaps a Category 4 hurricane, and it ended up - instead of re-intensifying over the Gulf of Mexico after it hit Cuba, it weakened, and it came ashore as a high-end Category 2. LANDSEA: Well, unfortunately, the wind-speed forecasts were not nearly as good. NORRIS: And what did they perhaps get wrong? So track-wise, we did a very good job on that one. Even out four and five days in advance, we were thinking about the central north Gulf Coast, in Louisiana, and that's where it ended up happening. LANDSEA: The track predictions came out exceptionally well. What did forecasters get right in that case, and what did they get wrong? NORRIS: First of all, let's talk briefly about Hurricane Gustav. CHRISTOPHER LANDSEA (Science and Operations Officer, National Hurricane Center): Good afternoon. He's the science and operations officer at the National Hurricane Center in Miami. Joining us to talk about that is Christopher Landsea. Still, as Hurricane Gustav showed, forecasters have a hard time predicting how strong a storm will be when it hits, and when it will actually hit. The art of forecasting hurricanes has evolved a lot over the past few decades.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)